|

Soon after entering World War 11

Australia was asked by Britain to accept and guard large numbers of

'enemy aliens' and prisoners of war. The British government felt that it

could not afford to feed large numbers of prisoners and it was believed

that once in Australia the internees would have no chance of escape.

Eager to show solidarity with

Britain's cause, Australia readily agreed and decided to place the

prisoners in a number of different camps scattered around the country

and guard them with reservists and soldiers too unfit to serve overseas.

Part of the enormous cost of housing and guarding the prisoners would be

borne by Britain.

|

|

|

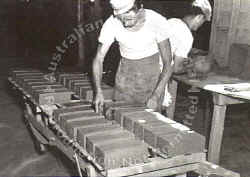

Hay,

NSW. 1944-01-13/14. 46604

Corporal B. Rivola, an Italian prisoner of war stacking wet bricks

on a barrow at the brick making plant operated by the Italian

prisoners of war at the 16th Garrison Battalion prisoner of war

detention camp. |

Yanco,

NSW. 1944-01-31.

A Jersey cow and her one day old bull calf being shown by Italian

prisoners of war (POWs) at No. 15 POW Camp. |

The prisoners came from everywhere.

There were large numbers of Italians captured in the various North

African campaigns, there were Japanese taken in the Pacific region, as

well as an indistinct group known as 'enemy aliens'. These latter

prisoners included many German Jews who had fled to Britain to avoid

persecution under the Nazis. They were imprisoned in response to a

widespread fear that they included German spies; ironically, many had

originally hoped to join the allied war effort where their many skills

would have been fully utilised.

The first large group of 'enemy

aliens' arrived in Sydney on 7 September 1940. They were taken to a camp

erected near Hay in the south of New South Wales. Here they found

conditions far more tolerable then anything they had so far endured.

Realising that their prisoners wanted to fight the Axis powers as much

as they did many of the Australian camp officials allowed the prisoners

a large degree of liberty.

Very swiftly a school was organised

and a theatrical group formed. Like prisoners everywhere, the 'enemy

aliens' felt a desperate need to keep busy, They received much help and

encouragement in their efforts from various Jewish groups in Australia.

When, eventually, the imprisonment of

these Nazi refugees was seen as a costly blunder, they were given a

choice of either working in Britain or staying in Australia until a more

acceptable location was found. By the end of 1941 few of the original

enemy aliens' from Germany remained in Australia.

|

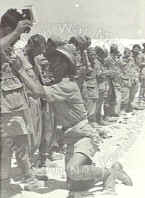

El Alamein,

Egypt. 1942-07-18. Italian

prisoners of war being searched by a provost of the 9th

Australian Divisional Provost Company. These prisoners were

captured by units of the 24th Australian infantry brigade during

operations on the night of 1942-07-16 to 1942-07-17, in the

battle area west of El Alamein.

|

By far the largest group of POWs held

in Australia were Italians. These included actual soldiers captured when

fighting in North Africa and merchant seamen who were interned when war

was declared. Altogether some 18 500 Italians were imprisoned in

Australia from May 1941 to December 1947 when the last group was

returned to Italy. A small band of escapees remained at large until

1952.

The first batch of Italian POWs was

also sent to the internment camp at Hay. Later further camps were built

everywhere from Gaythorne in Queensland to Brighton in Tasmania. The

Italians' initial response to their capture varied. Many were simply

glad to be out of the war zone as they had been conscripted into the

army and had no interest in Mussolini's plan for an Italian empire.

Others took their capture more

seriously. Some prisoners had been members of the Fascist Party and

believed it was their duty to Mussolini to try and escape. These

differing attitudes occasionally led to conflict.

ON THE FARMS

|

TOMATO

PICKERS |

|

Murchison,

Australia. 5 March 1945. View of Italian prisoners of war (POWs)

interned in C Compound, No. 13 POW Group, picking tomatoes on a

property in the Shepparton district where 740 Italian POWs work

daily. An Australian Military Officer is seen, middle background,

on a visit to the pickers to ensure maintenance of output.

|

Early in 1943 it was decided to use

the large number of Italian POWs in Australia to supplement the rural

workforce which had been depleted as a result of war service. The

prisoners were to be paid 10 shillings a week and their keep in return

for which they would work for a farmer. Even there the prisoners

remained under military discipline and were warned that any breaches of

regulations, such as sleeping with Australian women or not wearing their

prison uniforms, would be punished.

An army notice informed participating

farmers that the 'Italian prisoner of war is a curious mixture, in that

he can be made to give of excellent work if certain points are observed;

1. He cannot be driven but he can be

led.

2. Mentality is childlike; it is

possible to gain his confidence by fairness and firmness.

3. Great care must be exercised from

a disciplinary point of view or he can become sly and objectionable if

badly handled.'

|

These

Italian Prisoners of War are working on installing a new

filtration trench for the septic system at their POW Camp. |

WILLING WORKERS

The Italians turned out to be

generally keen and intelligent workers. Many rural Australians had never

met Italians before and found the experience enlightening. Some began to

learn Italian while others developed a liking for Italian food. Many

prisoners offered to cook at least one Italian meal a week.

One prisoner wrote to his family in

Italy: 1 am with a family of four: parents, a boy and a girl. I am being

treated just like in my own home. 1 have a room for myself with all the

comforts. 1 use their bathroom and basins, I eat with them and they do

the cleaning. In other words I am considered the third child of the

family.'

With the end of the war in August 1945

most of the Italian prisoners believed they would be sent home

immediately. But the first batch of repatriated prisoners did not sail

until July 1946 due to a lack of shipping and the very confused

political situation in Italy. Understandably, the vast majority were

keen to see their families and homes again, some of whom they had not

seen for six years. A large number, however, decided to return to

Australia and settle in areas they had seen or lived in as prisoners.

THE JAPANESE

Of all the prisoners housed in

Australia during the war the Japanese were undoubtedly the most bitter

and resentful. Under the Japanese rules of war (known as the Bushido

code) prisoners were disgraced persons. Every soldier had an obligation

to die for the Emperor and if the enemy succeeded in capturing him he

was expected to kill himself.

The Australian guards could not even

pretend to understand this attitude and saw most of the Japanese

prisoners as surly and fanatical. Things were not helped when late in

the war information reached Australia about the way the Japanese were

treating Australian prisoners.

It was this mutual incomprehension

between the two races which led to the 'night of a thousand suicides'

when the Japanese in the Cowra prison camp attempted a mass breakout on

5 August 1944. As a result, 231 Japanese and four Australians were

killed. The Australian guards thought the Japanese were attempting to

take over the camp. Actually, they were attempting to kill themselves.

The Australian guards could not even

pretend to understand this attitude and saw most of the Japanese

prisoners as surly and fanatical. Things were not helped when late in

the war information reached Australia about the way the Japanese were

treating Australian prisoners.

Yet there is no evidence to suggest

that the Australian authorities treated the Japanese prisoners any

differently to any other group. Unlike the Italians they were not

permitted to leave the camps to work on the farms but otherwise they

received the same rations and were subject to the same discipline. At no

time was there any attempt to wreak revenge on the Japanese for their

treatment of Australian prisoners. Unfortunately this attitude was

misinterpreted by some of the Japanese as weakness and on several

occasions they pushed matters as far as they could by refusing to work

when ordered, refusing to turn up on parades and refusing to salute

Australian officers. Had Australian prisoners acted in the same fashion

in Japanese POW camps their punishment would have been severe.

Some of this page is an extract from Front Line Dispatches. Bay

Books. ISBN 1 86256 287 3

|