|

| Category:

Conflicts/Others |

|

|

|

|

|

|

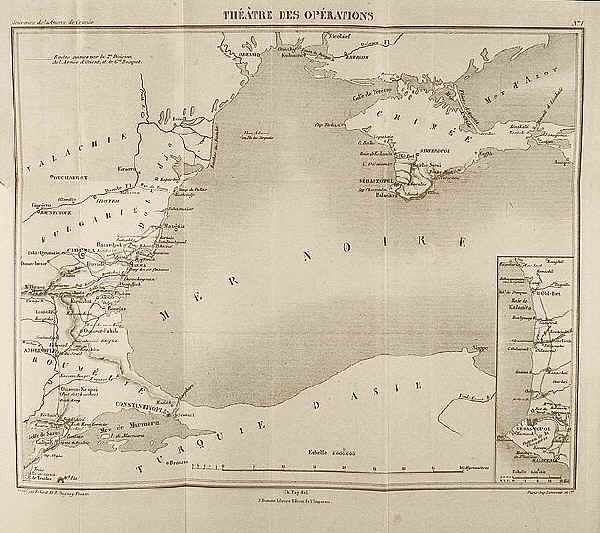

The Crimean War

1854/56 and Australian Involvement

|

|

In 1853, Russia sent troops to defend

Christians within the Ottoman Empire. Within months, Russian troops had

occupied parts of the Ottoman Empire and the Turks declared war on Russia

. On 28

March 1854, looking to prevent Russian expansion, Britain and France (with

Austrian backing) also declared war on Russia.

In September 1854, Allied

troops invaded the Crimea and within a month were besieging the Russian

held city of Sebastopol. |

|

| British Crimea

medal |

Turkish Crimea medal |

|

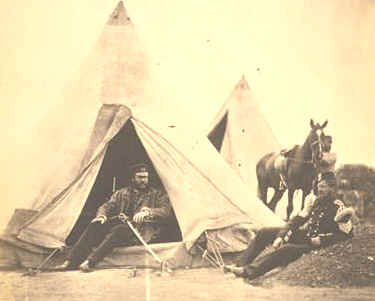

Sydney, NSW. c. 1880. Studio

portrait of Charles Dalton, wearing the uniform of the 8th King's

Royal Irish Hussars.

Born in London on 24 November

1832, he served in the Crimea and Turkey at Alma, Balaclava,

Inkerman and Sebastapol and took part in the charge of the Light

Brigade.

He also served in India at

the Siege of Kotah, recapture of Chundaree Kotah Ki Seari, capture

of Gwalior Powrie, Sindwah and Koonoyr.

He spent twenty five years in

charge of the Governor's Escort in New South Wales and died in

Balgowlah, NSW, on 5 February 1891.

His grandson 96 Sergeant

Trumpteter Clive M. Dalton, 4th Light Horse Brigade, died of wounds

received at Gallipoli on 12 August 1915 (Donor M.

Aspinall). |

On 25 October 1854, the Russians were

driven back at the Battle of Balaclava (including the foolhardy Charge of

the Light Brigade). Eleven days later, the Battle of Inkerman was also

fought (with high casualties on both sides). Poorly supplied and with

little medical assistance (despite the self-publicity of Florence

Nightingale), the British troops suffered immense casualties - 4,600 died

in battle; 13,000 were wounded; and 17,500 died of disease.

|

|

| On the obverse is a Young Queen

Victoria. On the reverse, a British Cavalryman charging over the

dragon serpent that is Russia. At the top of that is "TO

BALACLAVA!". This 1854 medallion is 23mm or almost an inch in

diameter. |

The French and British forced the fall

of Sebastopol on 11 September 1855 and peace was subsequently concluded at

Paris. Within fifteen years, the Russian were back in Sebastopol and

rearming.

|

| Interesting

Side Note 1:It was the first war where the electric

telegraph started to have a significant effect; the first 'live' war

reporting to The Times, and British generals' reduced

independence of action from London due to such rapid communications.

Newspaper readership informed public opinion in Britain and France as

never before.

|

Interesting

Side Note 2: The Crimean War occasioned the

invention of hand rolled "paper cigars" - cigarettes - by French

and British troops who copied their Turkish comrades in using old

newspaper for rolling when their cigar-leaf rolling tobacco ran out or

dried and crumbled.

|

|

| The Thin

Red Line - Original painting by Robert Gibb. The

93rd Sutherland Highlanders facing Russian cavalry at the Battle of

Balaklava 1854.

|

|

Diplomatic Prelude

As he had on other occasions, Nicholas I

tried again in 1853 to get an understanding with England about the

position of Turkey and to prevent a rapprochement between England and

France. The Russians would not tolerate the establishment of the English

in Constantinople, but did not want to annex the city either. Temporary

occupation by Russia might, however, be necessary to secure Russia's aim

of finally getting secure outlet from the Black Sea. In discussions with

Foreign Minister Russell of Britain Russia suggested an independent

Moldavia and Wallachia, a Serbia under Russian protection, and an

independent Bulgaria. The English were to get Egypt and Crete. The

Austrians could establish themselves on the Adriatic.

| Russell rejected the

"offer" and said that France would have to be consulted on

the matter.

Nicholas I, however, was under the

erroneous impression that some sort of "new system"

existed as a result of Nesselrode's Memorandum of 1844, which had

suggested a arrangement with regard to the Straits.

This particular memorandum and the

substance of the current diplomatic conversations with British

Ambassador Seymour in St. Petersburg were published by Britain and

touted as proof that "dark ambitions of a foreign despot"

were endangering the peace of Europe. |

|

Immediate Cause

The Franco-Russian dispute over the holy

places in Palestine was the immediate cause of the Crimean War. At the

time Turkey controlled Palestine, Egypt, and large chunks of the Middle

East. The Port (Moslem ruler of Turkey) had given privileges to protect

the Christians and their churches in the Holy Land to many nations. That

explains why so many different churches and nationals control various holy

shrines in Israel to this very day. At the time France and England had

gotten more specific commitments from the Port than other nations.

France's interest in Palestine had been stimulated by a domestic crisis in

1840-1841. Napoleon II pushed it because he relied on the support of

militant clerical groups in France. In 1850 Napoleon III requested the

restoration to French Catholics of the capitulations of 1740. This meant

that the French wanted the key to the Church of the Nativity in the old

city of Jerusalem and the right to place a silver star on Christ's

birthplace in Bethlehem. The French threatened military action if the

Porte did not give way and the Russians threatened to occupy Moldavia and

Wallachia if he did. The weak Porte did the best he could under the

circumstances and gave a yes answer to foreign parties. This bit of

typical Turkish duplicity was soon discovered. When it was discovered the

French send the warship Charlemagne to Constantinople and a squadron of

ship the Bay of Tripoli. In December 1852, having no other choice, the

Porte gave in to Paris.

In February Nicholas responded by mobilizing two army corps and sending

his ambassador, Menshikov, to Constantinople. Menshikov demanded not only

the restoration of Greek rights but also a secret alliance and the

protection of all orthodox laymen under Turkish rule-that meant some 12

million subject of the Porte. At this point the British got into the act

in the person of a very clever diplomatic operator in Constantinople by

the name of Stratford de Redcliffe. The latter outfoxed Menshikov who got

concessions on the Greek rights issue but non of the other demands. So

Meshikov went home.

It seems silly to us today that they argued over the keys to a church, but

then it was not just any church. And besides, the religious issue was not

the essential factor in the Franco-Russian dispute. France wanted to break

down the continental alliance that had paralyzed her for half a century.

National interests were involved here. England and France, in particular

responded to popular sentiment stirred up by liberal and patriotic groups

in their countries. Financial and trading groups, as always, were involved

as well. Such pressure is not evident in the case of Russia. The Black Sea

trade at this time was still quite insignificant.

When the Menshikov Mission became public

knowledge it strengthened the anti-Russian faction in the British cabinet.

So the British decided it was worth a war to keep and expand their

interest in the Eastern Mediterranean. In June 1853 an Anglo-French naval

force entered the Dardanelles. In July the Russian army invaded the

principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (modern day Rumania).

The war could still have been prevented. There were 11 different project

for pacification at the end of 1853. But the only important one was the

so-called "Vienna Note" to Turkey and Russia by France, Austria,

Prussia, and England. The Porte was to promise no change in the status quo

without the explicit consent of France and Russia. Russia accepted this

condition, but Turkey naturally rejected it. Nicholas I and Francis Joseph

of Austria even had a personal summit at Olmütz. Nicholas promised not to

intervene in Turkey or to extract some right to protect orthodox

Christians under Turkish, like in the famous Treaty of Kuchuck Kainardje.

The English, however, turned this deal down.

|

The following letter to the editor appeared in the SMH

early last century.

Sydney Morning Herald, Monday, May 1, 1911

THE OLDEST VOLUNTEER

(letter)

"TO THE EDITOR OF THE HERALD

Sir, I have noticed several letters in your paper claiming the above

title. During the Crimean War, in 1854, a volunteer force of

cavalry, artillery and infantry respectively was formed: I joined the

cavalry under Captain Macdonald, an Imperial officer from India. We

were sworn in and took the oath of allegiance by Major Cockburn at

his office which was then on the first floor at the southern end

where the Sydney Mint is now. I still have in my possession the

forage cap worn by me. We had to find our own uniforms, which were

expensive, as also horse and accoutrements. When peace was

proclaimed I joined the First infantry Regiment in 1867, and had

33.5 years' service altogether. I think it will be very difficult to

beat my claim, at all events, to be one of the oldest volunteers now

living.

I am, etc.,

J.H. MORRIS

Lieut. Col., V.D."

I found this soldier in the NSW Govt's "1894 BLUE BOOK" on page

50, as a

Major in the Military Forces - Infantry - 1st Regiment.

The Blue book states he joined the NSW Govt Military establishment on Feb

14, 1871 and was promoted to his then current position of Major on the Nov

15, 1888.

-

Can you please give me other information about this officer?

-

i.e. What other wars did he fight?

- when was he promoted to Lt Col?

- when did he leave the military?

- what is his military history?

- etc

Thank you for your assistance with this matter.

All the Best

J J Mitchell

|

|

The Crimean

War: an overview

from http://www.geocities.com/Broadway/Alley/5443/crimwar1.htm

In the years 1854 to 1856, Britain fought its only European war between

the ending of the Napoleonic conflict in 1815 and the opening of the

Great War in 1914. Although eventually victorious, the British and their

French allies pursued the war with little skill and it became a byword

for poor generalship and logistical incompetence.

The war began as a quarrel between Russian Orthodox monks and French

Catholics over who had precedence at the holy Places in Jerusalem and Nazareth.

Tempers frayed, violence resulted and lives were lost. Tsar Nicholas I

of Russia demanded the right to protect the Christian shrines in the

Holy Land and to back up his claims moved troops into Wallachia and

Moldavia (present day Rumania) then part of the Ottoman Turkish empire.

His fleet then destroyed a Turkish flotilla off Sinope in the Black Sea.

In an early instance of propaganda, British newspaper reports of the

action said the Russians had fired at Turkish wounded in the water.

Russian domination of Constantinople and the Straits was a perennial

nightmare of the British and with the two powers already deeply

suspicious of each others intentions in Afghanistan and Central Asia,

the British felt unable to accept such Russian moves against the Turks.

Louis Napoleon III, emperor of France, eager to emulate the military

successes of his uncle Napoleon I and wishing to extend his protection

to the French monks in Jerusalem allied himself with Britain. Both

countries dispatched expeditionary forces to the Balkans. The British

was commanded by Lord Raglan, who had last seen action at the Battle of

Waterloo; the French by General St. Arnaud and, after his death from

cholera, General Canrobert both veterans of France's Algerian wars.

The war began in March 1854 and by the end of the summer, the

Franco-British forces had driven the Russians out of Wallachia and

Moldavia. The fighting should have ended there, but it was decided that

the great Russian naval base at Sevastopol was a direct threat to the

future security of the region and in September 1854 the French and

British landed their armies on the Crimean peninsula.

From their landing beaches the allies marched southward to invest

Sevastopol. On the way they fought their first major battle. At the

River Alma, a Russian army tried unsuccessfully to prevent the Allies

crossing the river and scaling the heights beyond. The defeated Russians

retreated inland and as the siege of Sevastopol began a regrouped

Russian army hovered menacingly on the flank of the British army who

were using the inlet of Balaklava as its supply harbour. Sevastopol was

invulnerable to any kind of sea borne attack and her landward defences

were also formidable. Soon the major strong points in the defences, the

Redan, the little Redan and the Malakoff bastion, would become household

words in Britain.

As the British and French prepared their siege works the Russian army on

the British right flank struck. They were flung back at this the Battle

of Balaklava but only with great loss and the near annihilation of the

British light cavalry. A further attempt by the Russians resulted in the

Battle of Inkerman, a murderous fistfight fought out in a fog so thick

that sometimes the troops could only see a few yards ahead. again the

Russians were pushed back.

|

The war settled down

to one of spade and artillery as the Allies pushed their trenches

nearer the defensive lines of Sevastopol.

The winter of 1854-55 brought

great misery to the troops, particularly the British as their commissary

department was grossly incompetent and for months the men were

clothed in rags, cold, hungry and short of everything. |

The only bright light in this sorry

tale of official negligence and stupidity was the work of Florence

Nightingale who almost single-handedly drastically cut mortality rates

for the British wounded at the hospital in Scutari.

Finally, in early 1856, Sevastopol fell and the war was brought to a

conclusion by the Peace of Paris. |

|

Battle of Balaklava & The Charge of the Light Brigade |

|

as well as the less

well known but much more successful |

|

The Charge of the Heavy

Brigade |

|

It was the Russian army hanging on the

flank of the British that caused the second of the Crimean War's

battles, the Battle of Balaklava. North of Balaklava harbour was a

slight rise where the 93rd Highlanders had made their camp. Beyond this

there lay the South Valley, an open valley leading up to a higher

line of hills known as the Causeway Heights. The Causeway Heights looked

down on a narrower valley called the North Valley and beyond it the

Fedoukine Hills. It was in the North Valley that the greatest spectacle

and most tragic event of the war would take place - the charge of the

Light Brigade.

Along the crest of the Causeway Heights were a string of six redoubts

manned by Turkish infantry. On the morning of 25th October, 1854 they

were approached by a massively superior force of Russian troops well

supported by artillery. the Turks held their ground as frantic

messengers run back to warn the British. Unfortunately, the British

reacted very slowly and by the time they had started across the South

Valley the Turks were in full flight, four of the redoubts in enemy

hands and Russian cavalry was swarming over the Causeway Heights. Soon

they approached the 93rd Highlanders under the command of Sir Colin

Campbell , later famed for his relief of Lucknow in the

Indian Mutiny . Campbell ordered his men to stand firm and die if they

must in their places in the line. There could be no retreat as they were

all that stood between the enemy and the disorganized British camp. Hold

they did and in such a fashion that Times correspondent William

Russell, watching from the hills above, was moved to coin the immortal

phrase 'a thin red line tipped with steel'. Shortened to 'the thin red

line' his phrase came to forever symbolize the stoicism and

imperturbability of British troops when faced with superior numbers.

|

The Heavy Brigade and

their successful charge |

|

Though the Highlanders drove off the Russian cavalry on their front, a

larger body of Russian horsemen were moving up the North Valley in the

direction of the British H.Q.. Disturbed by the fire of a British gun,

they crossed over the Causeway Heights to the left of the Highlanders

and saw below them the Heavy Brigade, six squadrons of British heavy

cavalry from the Royal Scots Greys, the Inniskilling Dragoons and the

Dragoon Guards.

|

|

The Russians were a dense grey mass all wearing

yellowish-grey greatcoats and the British cavalry approaching them in

lines of absurd thinness must have seemed hopelessly fragile, even

effete, in their bright scarlet tunics.

They were led by the aptly named

General Sir James Scarlett, 55 years old, who had never ever commanded

troops in battle. He was to show this day that he had a certain flair

for such things. Taking his time to dress his men into perfect lines and

ignoring an order to charge immediately, Scarlett organised his

squadrons as if on parade. The Russian cavalry, from the slopes of the

Causeway Heights watched with incredulous fascination. There had been no

British cavalry charges so far in the war and only a fool would

countenance such an action now, against a much stronger enemy.

Scarlett's trumpeter sounded the charge and his men moved off. The Scots

Greys wore heavy bearskins, the Iniskillings and the Dragoon Guards

embossed helmets. If not the finest cavalry in the world they were

certainly amongst the best attired. As they drove into the Russian line

the red tunics seemed to disappear in a sea of Russian grey. There was

no room for fancy swordsmanship and the troopers hacked about them as if

with meat cleavers. The ferocity, execution and sheer arrogance of the

charge, however, were too much for the Russians and they faltered. Then

they broke and fled northwards back over the Causeway Heights.

- It was not the most spectacular charge ever made by British cavalry, but

it was probably the most effective.

As the Russians retreated and the

wounded were being carried back to camp, an A.D.C. of Lord Raglan the

British commander-in-chief trotted up and handed Scarlett a note. The

exhausted Scarlett read the note and quickly turned away to hide the

moistening of his eyes. The note read simply, "Well done,

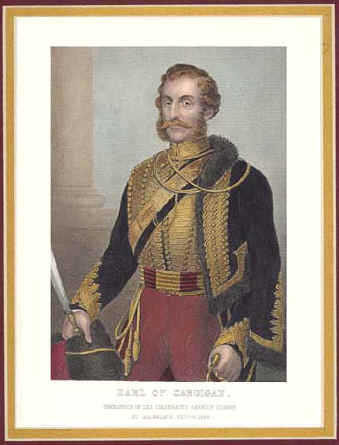

Scarlett." Raglan was not so pleased with Lord Cardigan, the leader

of the Light Brigade, who let had a golden opportunity slip by not pursuing

the Russians the Heavy Brigade had put to flight. The focus of the

battle now moved over to the western end of the North Valley were the

Light Brigade were positioned and a crucial factor came into play.

The

topography of the battlefield, with its hills and valleys, made it very

difficult for officers in the field to see much more than what was on

their direct front whereas the generals watching from the hills above

enjoyed an almost unimpeded view. As the Heavy Brigade reformed and

British infantry advanced on the westernmost of the captured redoubts,

Lord Raglan ordered Lord Lucan, the overall commander of the cavalry, to

take any advantage given and advance with infantry support to regain

possession of the heights. Lucan could see no sign of the promised

infantry support and declined to move. Lord Raglan fumed with impatience

at this inactivity and just then the critical event occurred. The

Russians brought up artillery horses to the captured redoubts obviously

intending to remove their guns. Determined not to allow this to happen,

Raglan sent Lucan an order telling him to prevent the removal of the

guns.

|

Lucan conferred with Cardigan, his brother-in-law and a man he heartily

detested. It was Cardigan's Light Brigade that would have to lead any

forward movement. Unfortunately, the only guns that either of them could

see were the Russian artillery, a mile away, at the eastern end of the

North Valley.

Supported by massed infantry and cavalry and with other

guns and riflemen on both sides of the valley, the Russian position was

unassailable - a three-sided trap like the jaws of some ferocious beast.

Cardigan mildly protested at the folly of charging such a position, but

Lucan reminded him that he had a direct order in writing from the

commander-in-chief. Unwilling to disobey a direct order, neither Lucan

nor Cardigan made any attempt to verify whether Raglan really wanted

them to make such a suicidal effort.

|

|

The Light Brigade and

its spectacular and disastrous charge |

Cardigan sounded the charge and the

Light Brigade started forward. The first line consisted of the 13th

Light Dragoons on the right, the 17th Lancers on the left and the 11th

Hussars in support. The second was formed by the 4th Light Dragoons and

the 8th Hussars. Cardigan rode well in front of the first line and for

all his faults there is no doubting his courage. 673 men rode forward

when the trumpet sounded. Less than 200, almost all of them wounded,

would return.

For the first fifty yards nothing happened and Lord Cardigan in his blue

and cherry coloured uniform and gold trimmed pelisse looked, as Lord

Raglan said, "as brave and as proud as a lion." Then the

Russian guns opened up. The horses began to move faster from a trot to a

canter to a gallop and the officers had trouble restraining some of

their men from spurring on ahead. From three sides a storm of lead and

iron winnowed the ranks of the British. The spectacle was incomparable

and on the hills above a British officer burst into tears at the sight

of such a suicidal tragedy. An elderly French general trying to comfort

him said, "Pauvre garcon. Je suis vieux, j'ai vu des batailles,

mais ceci de trop." Barely fifty men of the first line reached the

Russian guns. They rushed past, slashing at those gunners who had been

slow to find cover, and slammed into the Russian cavalry behind the

guns. They drove it backwards in disorder until overwhelming numbers

slowed the momentum of their charge and they were forced to retire. The

second line slaughtered the Russian gunners and pushing forward were met

by the remnants of the first line in retreat.

For the first fifty yards nothing happened and Lord Cardigan in his blue

and cherry coloured uniform and gold trimmed pelisse looked, as Lord

Raglan said, "as brave and as proud as a lion." Then the

Russian guns opened up. The horses began to move faster from a trot to a

canter to a gallop and the officers had trouble restraining some of

their men from spurring on ahead. From three sides a storm of lead and

iron winnowed the ranks of the British. The spectacle was incomparable

and on the hills above a British officer burst into tears at the sight

of such a suicidal tragedy. An elderly French general trying to comfort

him said, "Pauvre garcon. Je suis vieux, j'ai vu des batailles,

mais ceci de trop." Barely fifty men of the first line reached the

Russian guns. They rushed past, slashing at those gunners who had been

slow to find cover, and slammed into the Russian cavalry behind the

guns. They drove it backwards in disorder until overwhelming numbers

slowed the momentum of their charge and they were forced to retire. The

second line slaughtered the Russian gunners and pushing forward were met

by the remnants of the first line in retreat.

Lord George Paget, commander of the

second line, on being informed that Russian lancers were closing in

behind them shouted, "Halt boys, halt front, if we don't halt now

we're done!" His men obeyed and turned their weary horses back down

the valley up which they had charged at such cost. As they retired the

Russian lancers seemed to part to let them through with just a few

desultory lance prods to see them on their way. Some said this was a

Russian gesture of respect for the heroism of the charge. Some said it

was the result of the ineffectual leadership that was apparent in the

handling of Russian cavalry. Perhaps it was simply the ordinary Russian

troopers disdaining to risk their lives against an obviously spent force

that had shown such a proclivity to insanity. More than 500 British

horses died in the charge and it's possible the Russians just felt sorry

for the surviving mounts.

The

Battle of Balaklava was claimed as a victory by the British but in

reality it was not so. British cavalry played were unable to play any

significant role for the remainder of the war and the Causeway Heights

were left in Russian hands. This would greatly add to the misery of the

British Army as it faced the Crimean winter. |

|