| During the

Crimean War 1853-56

the South

Australian colonial government passed the Militia Act 1854 enabling it

to select men by ballot to undergo four weeks military training

annually. In fact, the forces raised were volunteers, and, until the

Defence Act of 1894, it was unclear whether they legally remained

civilians, albeit in uniform.

That Act provided that the members of the

volunteer militias were 'soldiers' who were subject to military

discipline, and liable to serve in any Australian colony. Amendments in

1896 allowed for compulsory military service should a state of emergency

be proclaimed. However, conscription by ballot was only to be used after

a call for volunteers. In the event, the ballot was never used and the

South Australians who fought in

South Africa 1899-1902

were volunteers.

As early as July 1901, the possibility of universal

military training was discussed in the new Federal Parliament. The

Commonwealth's Defence Act of 1903, as amended in 1911, provided for

universal military training. This was strongly opposed by many South

Australians. An account of the work of the Australian Freedom League, an

organization founded by the South Australian Quakers in co-operation

with other interested Christian groups, can be found in Charles

Stevenson's publication, The

millionth snowflake; the history of Quakers in South Australia.

The Library's archival collections contain detailed

information about the unsuccessful attempts of two brothers, Llewellyn

and John Jarman of Kingston in the south-east, to be exempted from the

military service. Records include the brothers' personal

papers, court

applications, legal

advice, newspaper

articles and letters

to the editor.

Although

the Defence Act required men to undergo training with the militia, it

specified that no Australian (including members of the regular military

forces) could be compelled to serve overseas.

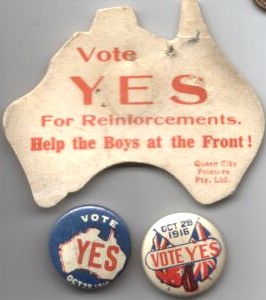

Following the outbreak of the First

World War in August 1914, initially volunteers flocked to the

Australian Imperial Force (AIF) for overseas service. By 1916 there were

insufficient new volunteers to cover the AIF's massive casualties and

to meet the British authorities requests for reinforcements. The Prime

Minister, WM Hughes, directly

appealed to all eligible men to volunteer. His plea was supported by

the work of patriotic

organisations, and a campaign of propaganda

posters, to raise more volunteers.

|

When it appeared that the recruitment targets would

not be met, the government sought approval, by way of a referendum on

October 1916, to require men conscripted into militia training to also

undertake overseas service. The referendum of 28 October 1916 asked

Australians:

Are you in favour of the Government having, in

this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in

regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this War,

outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service

within the Commonwealth? |

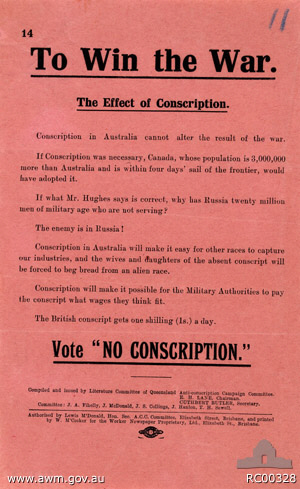

| Colour

leaflet against conscription.

"To Win the War. The Effect of Conscription. Conscription in

Australia cannot alter the result of the war.

If Conscription was necessary,

Canada, whose population is 3,000,000 more than Australia and is

within four days' sail of the frontier, would have adopted

it.

If what Mr. Hughes says is

correct, why has Russia twenty million men of military age who are

not serving?

The enemy is in Russia!

Conscription in Australia will make it easy for other races to

capture our industries, and the wives and daughters of the absent

conscript will be forced to beg bread from an alien race.

Conscription will make it

possible for the Military Authorities to pay the conscript what

wages they think fit. The British conscript get one shilling (1s.)

a day. Vote 'NO CONSCRIPTION'. |

|

|

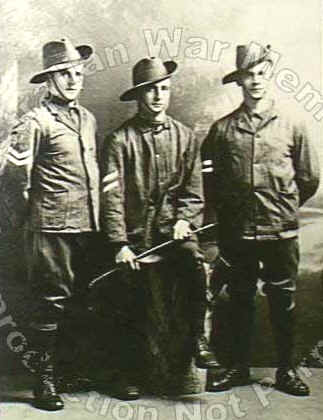

Conscripts of WW1

Studio portrait of new

recruits Corporals Arthur Gray, Richard E. A. Gray and David J.

Denny at "Billy Hughes" Training Camp at the Goulburn

showground, in Goldsmith Street.

Note their soft cloth jackets. The

Billy Hughes training camp was a second camp started for those

compulsorily called up, as the Federal Government was certain its

conscription referendum would be passed.

The AIF drilled in blue

dungarees and the "Hughesiliers", as they were facetiously

called, in yellow [probably light khaki].

When the referendum was defeated

most of the Hughesiliers went back to civilian life and some

enlisted. (Original print housed in the AWM

Archive Store) (Donor E. Bridge)

|

As there were 1,087,557 in favour and 1,160,033

against the referendum failed. Of the Australians who voted, 57.6 per

cent of South Australians opposed conscription; only New South Wales

recorded a stronger 'no' vote.

|

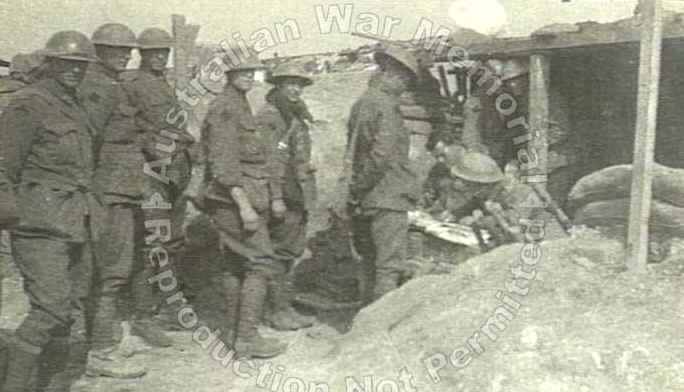

|

Members of the

21st Battalion queuing to vote at the second Australian

conscription referendum, while in front line supports at

Vaulx-Vraucourt-Bullecourt sector. |

The conscription issue was fiercely debated and

created bitter divisions between supporters and opponents. The flavour

of the disputes is given in letters written to relatives by two South

Australians convalescing in England after active service.

Jack Jensen, in a letter

to his Aunt Hannah dated August 1915, wrote,

"I would not like to be sent back to Australia

before the war is over. You see so many going about who will not

enlist & the excuses they give would make your hair turn grey. One

young chap who was asked to join said what had he got to join for. He

had no wife no children & no parents depending on him so why

should he fight let those fight who had something to fight for. These

sort of men make you feel ashamed & you want to get away to your

own men again.

Of course the prospect of getting wounded again or

killed is not very pleasant but I have seen some of my best mates

killed & they died like men & if I can do the same I will be

quite satisfied to go now. We all know we must die some time. If I am

wounded again I will be able to bear it as I did the last time &

if I am crippled I shall have to bear it as many another young chap is

doing & I shall know at least that I have done my duty to the

country which I have got my living in".

Contrast this with the letter

of Victor Voules Brown written much later on 19 May 1917.

"Last time you wrote you wanted to know why it

was the troops in France did not vote for conscription. I told you as

short as I could perhaps it was censored so will tell you again. To

cut it short the boys in France have had such a doing of it, that they

consider it murder (or near enough to it) to compel anymore to come

from Aussie. And then again they consider once conscription is brought

in it is the end of a free Australia (No doubt about it John Australia

is the finest country in the world to my idea.

When the vote for

conscription took place I was in Codford & I voted yes, but dinkum I

am like the rest now I have seen it, & wouldn’t compel anyone

(barring the few rotters of single chaps that won't come. And of course

to get them one would have to get a lot of others, so under the

circumstances let them stop at home. It is no good for a peaceful life

over there & I can tell you I am not looking forward to the next

dose".

A decisive defeat of the second referendum on 20

December 1917, which proposed,

"Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth

Government for reinforcing the Commonwealth Forces overseas?"

ended the issue of conscription for the remainder of the First World

War.

The Scullin Labor government 1929-32 abolished

compulsory military training so, on the outbreak of the Second World War

in September 1939, the conservative government led by Robert Menzies,

chose to reintroduce the measure. All single men on turning 21 were

required to undertake three months training with the militia to prepare

them for home defence. Over the next two years the military position

greatly worsened. The Japanese successes in the Pacific meant that

Australia faced a serious threat of invasion. The Labor prime minister,

John Curtin (an opponent of conscription in the First World War) in

February 1942 expanded the definition of 'home defence' to cover the

south-west Pacific.

There was again a public debate of the conscription

issue. The flavour of this is given by selected material in the

Library's collection. The case against conscription was set out by South

Australian trade unionists. The case for was put by the Australian War

Services League and in a pamphlet produced by the Adelaide Advertiser.

By contrast with the First World War, an overall

majority of Australians supported Curtin's proposals; South Australia

was one of four states where a majority approved conscription for this

broadened 'home defence', which was, of course, conscription for

overseas service in the areas where Australian forces were needed.

The

conscripted militia forces in fact played a vital role in the Pacific

war.

For a short period after the Allied victory in 1945,

conscription became a non-issue. For a short period after the Allied victory in 1945,

conscription became a non-issue.

The development of a 'cold war' between

the Western powers and the countries of the Soviet bloc led the

conservative Menzies coalition government to introduce yet another

conscription scheme with universal national service for 18 year old men.

Conscripts were not part of the Australian forces who served in Korea,

Malaya and Borneo.

From 1954 communist North Vietnam and South Vietnam

were at war. In the 1960s hundreds of thousands of United States troops

were involved in support of South Vietnam and the Australian government

also decided to commit troops.

A new National Service Act of 1964 required 20 year

old men, selected by a ballot of birthdays, to serve for two years in

regular army units. In May 1965 the Defence Act was amended to provide

that these conscripts could also be required to serve overseas. Between

1965 and 1972 (when the last Australian troops were withdrawn from

Vietnam) over 800,000 men were registered for National Service, 63,000

were conscripted by the ballot, and some 19,000 served in Vietnam..

There were 200 killed and 1,279 wounded.

Many Australians were opposed

to involvement in the Vietnam War and even more objected to the use of

conscripts there. The first conscript to die in Vietnam, Errol Noack,

was a South Australian. Groups such as the Campaign

for Peace in Vietnam campaigned vigorously against conscription, and

thousands joined protest marches in Adelaide.

Many young men refused to register and were supported

by citizens opposed to conscription. Two conscientious objectors

arrested for refusing to register were John

Zarb and Robert Martin and both were jailed. Robert

Martin talks of his experiences in an oral history recording held in

the Library's archival collections.

Extracted from http://www.slsa.sa.gov.au/saatwar/ConscriptMain.htm |