|

| Category: Western

Front |

|

|

|

|

|

| The

Somme: graveyard of armies |

|

Page index

|

| The Somme

campaign into which the Australians would soon be drawn began on 1 July

1916 after a bombardment of 7 days.

British and French armies

attacked 20 miles east of Amiens with the aim firstly of breaking

through the German line.

The gap in the enemy line would then

allow a British 'Reserve Army' of cavalry to push through and 'roll-up'

the German line north of the breach towards Douai and take the enemy in

the rear.

The British troops were

extraordinarily brave and determined. |

| When

the artillery barrage lifted the crowded trenches emptied and the

soldiers of Britain's New Army, laden like beasts of burden, staggered

forward to suffer stupendous losses, amounting to nearly 60,000

in a single day.

They suffered sacrificial losses

because of the persistence of the High Command in renewing useless

assaults.

French Somme

Veterans Medal. The obverse shows two warriors with spears and shields

fighting side by side. On one shield is a cockerel, representing France,

and on the other shield is a lion, representing Britain and the

Commonwealth. Above the warriors is a nymph which represents the Somme.

The figure is reclined with her left forearm resting on an urn, out of

which flows the river. |

|

|

VC Corner Cemetery in

the Fromelles area is unique.

410 men of the 61st British

and 5th Australian Divisions lie in a mass grave. On the rear wall

is inscribed the names of a further 1,298 Australian soldiers who

lost their lives in this area and who have no known grave. |

In

support of the massive Allied offensive on the Somme River, the British

staff had decided that a strong feint attack would be made at Fromelles,

some 50 miles north of the river. This attack was expected to deter the

Germans from rushing troops from that region to the area of the main

Allied thrust on the Somme. An attack would be made from the 'nursery'

near Armentieres, employing two divisions to seize the 'Sugar Loaf'

salient near-Fromelles.

The 5th

Australian Division which had only just moved into the 'nursery' was

therefore ordered, with the British 61st Division, to attack the 'Sugar Loaf'. The Australian 1st,

2nd, and 4th Divisions were to take part in the main Somme offensive and

had been ordered to be in the area of Amiens by 13 July.

The

attack towards Fromelles was preceded by a seven-hour artillery

bombardment which began at 11

am on 19 July. It was a bright summer day and the Australian troops,

although comparatively inexperienced, were in fine form. They cheered as

they saw the artillery barrage blowing German parapets into the sky.

At 6 pm

with two and a half hours of daylight ahead, the advance began. The 8th

Brigade, although new to front line experience were well trained. Many

Australians were killed and wounded but most of the enemy fled as the

Brigade approached the German breastworks. The 14th Brigade crossed the

enemy lines more easily and quickly captured the German front trench. The

15th Brigade, however, fared badly. The bombardment had not been effective

and the enemy managed to man their machine guns immediately the

bombardment ceased. The 15th was shot to earth. Line after line were met

by a tempest of fire as they emerged from the remains of an orchard.

The 61st

Division, attacking on the other face the 'Sugar Loaf' had been heavily

hit by enemy artillery and machine gun fire. Its battalions reached the

German line only at isolated points from which they were soon driven out

again.

Between

them the 8th and 14th Brigades captured 1000 yards of the enemy front

trenches, but because of the heavy losses suffered by the 15th Brigade,

the right flank of the 14th Brigade was exposed to intense fire from the

'Sugar Loaf'.

That

night, the 7th Bavarian Division facing Australians, mounted

counterattacks. By 5.45 next day after fierce and confused fighting, the

8th Brigade had been forced from the German lines by 8 am the 14th Brigade

was ordered to withdraw. The Australian trenches were now packed with dead

and dying. It was a tragic beginning for the newly formed 5th Division.

Its casualties, in a battle lasted only one night and a few hours

preceding it totaled 5,533 of whom 400 were prisoners. Man, the wounded

still lay out in no-man's-land.

The 5th

Division was crippled by the reverse at Fromelles and would not again be

ready for offensive action for many months. The official communiqué

masked the dimensions of the disaster by describing the battle as

'important raids' during which "about 140 German prisoners were

captured.'

C

E W Bean, the Australian

historian commented: 'The value of the result, if

any, was tragically disproportionate to the cost.'

|

|

Re-creation of a

German trench using actual artifacts from WW1 |

The Somme

battle which had begun on 1 July 1916 was the bloodiest of the whole war,

with the soldiers enduring unimaginable horrors. Three weeks after the

battle was joined the Anzacs were committed to action before Pozieres,

north of the Somme River. The artillery bombardments which fell on them

there were the heaviest and most prolonged they were to experience. At

times the barrages could be heard in England. Pozieres, once a prosperous

village, became a gigantic ash heap of waste, torn to shreds by a tornado

of shells and littered with mangled bodies.

The

big attacks on the Somme on 1 and 14 July, though they had cut into the

German defences, had not led to the breakthrough Haig had hoped for. Between

13 and 17 July four attacks had been made against Pozieres,

by British infantry, but there had been little to show for these desperate

efforts except crumpled bodies of soldiers hanging on the barbed wire

entanglements. General Gough, who commanded the Reserve Army, called Major

General (Sir H B) Walker, the commander of the 1st Australian Division,

and told him: 'I want you to go into the line and attack Pozieres tomorrow

night.'

As

the Australian battalions filed towards the village some of the men were

gassed by phosgene fumes. After a heavy bombardment the 1st and 3rd

Australian brigades attacked at 12.30 am on 23 July. They quickly seized

the front German position and in succeeding stages reached the main road

through the village, killing or capturing the German garrison. A

counterattack by a German battalion at dawn was shot to pieces by the

Australian machine gunners.

The Australian effort

at Pozieres was a striking success. The main buttress of the German line

on the battlefield had been broken. Yet except for the Pozieres region,

Haig's great battering-ram effort on the Somme had failed.

For the Germans,

Pozieres was a key bastion and they were determined to regain it. As a

preliminary they unleashed an artillery barrage which deluged the whole

area. Australian and British artillery replied with a maximum counter

effort.

Because of the

saturating bombardments it soon became clear that the 1st Division, which

had lost 5,385 officers and men was at the end of its endurance. The

original plan had called for the 1st Division to push on and seize the OG

(Old German) lines beyond the village. But that task was now seen to be

impossible. An attempt by the 5th Brigade of the 2nd Division to seize a

section of the lines failed. When the 1st Division came out of the line

'They looked,' wrote a sergeant of the 4th Division, 'like men who had

been in hell ... drawn and haggard and so dazed they appeared to be

walking in a dream.'

By 27 July the 2nd

Australian Division had taken over the whole front at Pozieres. The 2nd

had never fought a pitched battle but they had served on Gallipoli and

were therefore 'old hands'.

The Germans, watching

the preparations for a new offensive effort, systematically and endlessly

pounded the Australians with artillery and in one heavy concentration part

of the 24th Battalion was annihilated. 'The shelling of Pozieres,' wrote

historian Bean, 'did not merely probe character and, nerve; it laid them

stark naked as no other experience of the AIF ever did.

On 28 July, the 7th

Brigade was assigned to form the centre of the attacking force between the

5th and 6th Brigades. But the attack failed with the 2nd Division losing

some 3500 men. One of the great difficulties in night attacks was that in

the uproar, the confusion and the blackness soldiers could not find their

way. Digging jump-off trenches from which attacking troops would begin

their advance was an almost impossible task. A famous letter written at

this time by Melbourne journalist Lieutenant J. A. Raws, who, with his

brother, was killed in the Somme battle, described the battle scene. No

account of the horror of Pozieres is likely to equal this description

written by Raws:

... we lay down

terror-stricken along a bank. The shelling was awful ... we eventually

found our way to the right spot out in no-man's-land. Our leader was shot

before we arrived and the strain had sent two other officers mad. I and

another new officer took charge and dug the trench. We were shot at all

the time... the wounded and killed had to be thrown to one side ... I

refused to let any sound

man help a wounded man; the sound had to dig ... we dug on and finished amid

a tornado of bursting shells ... I was buried once and thrown down several

times ... buried with dead and dying. The ground was covered bodies in all

stages of decay and mutilation and I would, after struggling from the

earth, pick body by me to try and lift him out with me and find him a

decayed corpse ... I went up again the night and stayed up there. We were

shelled to hell ceaselessly. X- went mad and disappeared... there remained

nothing but a charred mass of debris with bricks, stones, girders and bodies

pounded to nothing ... we are lousy, stinking, unshaven, sleepless ... I

have one puttee, a man's helmet, another dead man's protect dead man's

bayonet. My tunic rotten with other men's blood and partly spattered with

a comrade's brains.

|

| Mouquet

Farm |

for

details for

details

|

|

|

Some Diggers called

this place Moo Cow farm. Others called it Mucky Farm.

The 2nd Division

had won the battle but at great price. It was exhausted and its losses

had been heavier than any other Australian division had suffered

in one tour in the line. In 12 days losses totaled 6,848 officers and

men. Five of its battalions each lost between 600 and 700 men. Many

wounded, waiting for their wounds, were shaking like aspen leaves, a

sure sign of overstrain caused by shell fire.

The division's

infantry was withdrawn on August 7 and replaced by the 4th Australian

Division.

The Australians were

now ordered to attack north from Pozieres towards Mouquet Farm. After a

series of engagements it was not until September, after the British had seized

Thiepval and swept past Mouquet Farm, that it fell.

In October the

autumn rains set in. The battlefield became a vast bog and active

operations petered out. Roads became impassable and the troops crossing

battlefield sank deep into the mud, which drastically slowed their

movements. The Australian Divisions caught in the morass would now spend

their most difficult months of the war.

In November,

two attacks were launched, one near Gueudcourt and the other near Flers.

In both attacks the Australians succeeded in

entering enemy trenches. But the battlefield had dissolved into a

quagmire and the terrible struggles of soldiers

through the mud caused great exhaustion. Haig now decided that for the

remainder of the winter only small attacks and raids were possible and

so the campaign ended.

The charnel house of

the Somme was the hardest and bloodiest campaign fought by the British

in the war. British casualties totaled 410,000 including the flower of

British youth in the New Army. French losses were 190,000. German losses

were not much less than the combined Allied total.

Haig had

gained little territory for the prodigious effort. A strip of France

only 30 miles long and with a depth of 7 miles had been conquered. It

was clear however that the German pressure on Verdun had been relieved.

As well, the Germans had been placed under intolerable strain and unmistakable

signs appeared of the deterioration in the German

Army. A steady

trickle of German deserters was coming across the lines.

The Australian

soldier in France never forgot the

misery, the pain and the slaughter of the Somme.

Including the devastating result of the feint at Fromelles, the

Australian divisions in seven weeks lost a total exceeding 28,000

officers and men. Their resilience and staunchness had been subjected to

the severest possible strain. But they survived and it was not long

before the old Digger spirit, with all it's elasticity, emerged from the

dreadful experience.

Text

from ARMY Australia, The Australian Defence Force Series, by George

Odgers. |

|

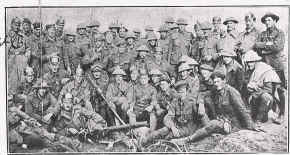

1st Auckland Infantry Battalion

at the Somme |

1st Auckland Infantry Battalion after the Somme Battle

'A Tale from the Trenches'

No: 12/2824 Private Basil "Puller" Pulford was a sniper in the 6th (Hauraki) Company, 1st Auckland Infantry Battalion. He served on Gallipoli, and later took part in the Battle of the Somme.

After the fighting of that dreadful July day in 1916, he was the last member of the Hauraki Company to be accounted for, and had been given up for dead. He was a farmer from Thames and his mate's Harry Murray and Stan Danby were in the trench counting the cost of all of the Thames men who had been killed. Stan's brother Walter Danby was amongst those missing, later confirmed killed. They were asking "Has anyone seen Puller (Rifleman Pulford)?" no-one had and some-one quietly

murmured "Poor old Puller, he's gone West too."

Shortly after they heard a metallic sound and then a thump into the bottom of the trench, they were surprised and immediately Stood-To. When they looked down at where the object landed they saw a sand bag lying in the trench.

About a minute later they heard a whispered "Don't shoot Harry, it's me Puller, I'm back." and with that Rifleman Pulford slid down into the trench to join them. He was covered in mud and had been unable to retire, as he was under fire from several machine guns so he had waited until late into the night.

Inside the sandbag was a host of battlefield souvenirs including several Iron crosses, badges, buttons etc. He also had a complete German uniform.

After the war he mounted all of the badges and buttons onto a wooden shield and this was in the family homestead for many years. After his death, the shield and the

Pickelhaube helmet were loaned to the Thames Returned Services Association Clubrooms where they remained until the recent closure of that establishment in July 2005.

11 Divisions of the British Empire attacked that day, and although a number of units managed to reach the German trenches, they could not hold the ground and were driven back. By the end of the day, the British had suffered 60,000 casualties, of whom 20,000 were dead: their largest single loss of the First World War. Sixty per cent of all officers who attacked on that first day were killed. The Battle of the Somme raged from 1 July 1916 - 13 November 1916. The battle ended in mid-November with both sides having exhausted their armies, and the British (and Allies) having only advanced some five miles. The final toll of the Battle was Britain suffered around 420,000 casualties, France 195,000 and the Germany around 650,000.

The following photo is from a New Zealand WWI periodical showing men of the 1st Auckland Infantry

Battalion who were unwounded after the Somme. In the larger picture, the man standing, just left of centre with an X is Private Basil Pulford, (my wife's grandfather). He is wearing a German soldiers trench coat, and on his head is the soft cover for a German

Pickelhaube helmet; he had shot the previous owner. The X on the ground in front shows one of the officer's holding the helmet. The CO Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Plugge CMG (Plugge's

Plateau of Gallipoli fame), is standing just to the right of centre

front with an X on his chest.

Note: An Infantry Battalion usually numbers about 1,000 men.

An Infantry Company usually numbers about 120 men.

|

|

The photo also shows one of the unwounded men of Number 3 (Hauraki) Company of the Battalion who came out unwounded. Private Basil Pulford is standing on the very left dressed in a complete German uniform, helmet, coat and belt, he has XB written on his chest .

The OC, Captain C.A. Herman is seated in the centre with an X on his chest. |

| Webmasters

note. This image proves that the Germans were wearing the 'Coal

scuttle" steel helmet and the Pickelhaube in the trenches at the

same time. |

|

© Copyright Mike Subritzky 2005. Used

with permission |

|